The Silent Takeover: Later IPOs and The Reallocation of Tech’s Spoils

Who loses and gains from later technology IPOs? Exactly who you think…

The modern technology start-up is the greatest and most explosive wealth-generating machine to have ever existed. With so much money at stake, there are certainly many trying to get a bite at the (next) Apple.

But, given the stakes, has the investment market for late-stage (6-12 year old) technology companies evolved fairly? Who is reaping the upside for technology start-ups as they turn into real companies? What is happening to access, fees, transparency, and liquidity of the shares of these companies? Is the market healthier today than it was in the past? Are any entities exploiting the current late-stage market for their own gain at the expense of other market participants?

These are important questions, and given the amount of money at stake (read: all of the money), if a brave soul asked those questions, I wouldn’t interrupt...

Tech IPOs are Happening Later and Later

Most of the current leading technology companies of today were public companies before most of their value creation. Someone that invested $10,000 into each of the Magnificent Seven companies in the public market in the month after their IPO, and had the diamond hands to hold until March 2024, would have made, assuming reinvestment of dividends:

Apple (1980): $22,598,349 (actually higher, back-test only went to January 1986)

Microsoft (1986): $40,496,959

Amazon (1997): $7,185,261

Netflix (2002): $7,722,634

Google (2004): $312,826

Tesla (2010): $990,180

Facebook (2012): $182,607

The “Later and Later” technology IPO trend that began with Google and continued with Facebook has now become common in the marketplace (See Jay Ritter’s excellent study here). Six-to-eight years of being private have turned into ten-to-twelve years.

There are roughly 1,200 private companies now valued above $1 billion, a valuation higher than the average of the pre-Google IPO valuations in the Magnificent Seven (Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, and Netflix). See below for the inflation-adjusted sizes in terms of market capitalization of the Magnificent Seven companies at the time of IPO:

Apple (1980): Approximately $403 million

Microsoft (1986): Approximately $1.17 billion

Amazon (1997): Approximately $1.03 billion

Netflix (2002): Approximately $602 million

Google (2004): Approximately $43.35 billion

Tesla (2010): Approximately $2.65 billion

Facebook (2012): Approximately $152.12 billion

Notice the trend? Who wins and who loses from companies staying private longer than they used to? Let’s jump right into it…

Who Loses

Investors

Investors care about access, low fees, and liquidity. Both public (by not being able to invest in companies) and private (by having to pay 2/20% to invest in the companies through a fund) investors are worse off because companies remain private for longer:

Investor access is worse. In a well-functioning market, as many investors as possible have access to the widest range of opportunities at low cost (without paying gatekeepers for that access). Public markets are open to all. Funds are only open to a more limited pool of accredited investors with some only accessible by qualified purchasers.

Fees are worse. Public shares do not have any ongoing fees for investors. Funds have management and incentive fees. Funds usually charge a 2% annual management fee and capture 20% of the appreciation of the companies through incentive fees.

Shares are locked up in funds instead of being freely tradeable. In public markets, investors can sell their shares in a marketplace and “exit” whenever they want. Ten-year lock-ups within funds (or individual locked-up positions until an exit) are worse for investors relative to freely traded, liquid public shares.

Employees

Employees are also worse off because they have to wait longer to sell their shares for cash and their common shares are not treated equally in private markets:

Employees wait significantly longer to “cash out”. Employees would rather receive liquidity by converting their shares into cash in a shorter time period. The longer they wait for the liquidity received in the public markets, generally, the worse for employees.

Their shares are not treated equally in private markets. A market is fairer when the underlying asset is fungible (tradeable 1-for-1). When a company goes public generally all shares convert into the same type (common shares) and there are regulations around the equal treatment of shares to protect shareholders. But shares in the private market are not fungible and shareholders are not protected. There are different share classes, with investors negotiating unique, favorable terms through preferred share classes. How do you think that ends up for the common shareholders (employees)? Not well. If only there was a giant pool of capital that would be willing to invest in common shares...

The Health of the Market

Well-functioning and healthy markets have competition, open access, transparency, and liquidity. The public market has these things, but the private market does not:

Price discovery is worse in private markets. The more market participants with a view on the price, the better that price is (the power of price discovery). A company has a fair price, whether it is traded privately without liquidity or publicly with liquidity. The marketable price (what someone can get for selling or buying their shares) is more likely to be closer to the fair price if there are more market participants “voting with their feet,” nudging the marketable price towards the fair price. The public market has more voters due to its significantly greater liquidity.

Private markets are opaque. Public markets are transparent. In private markets, it is difficult to know the real value of a company and asymmetric information leads to investors “in-the-know” having real advantages over those that don’t. These investors “in the know” know very well how different companies are performing and have advantages over other investors who don’t. While insider trading is still illegal in private markets, it’s way less enforceable than in public markets.

Neutral

Companies

A company is its own entity. There is always some separation between the company and the people running it, because one is a legal entity that lives in a filing cabinet in Delaware, and the others have human bodies and do human things. That is fine, just the reality. I too am a human.

A company has a fair price or valuation, and it just wants to grow. This company’s fair price is its fair price, which makes it somewhat feel neutral to whether it is traded privately or publicly. A bad company is a bad company, a good company is a good company, and no amount of liquidity in the public markets or illiquidity in the private markets can change that fact.

The volatility of a company’s stock price is also irrelevant to its fair price. One of the largest complaints against public markets is the volatility of having a day-to-day reminder of the market’s perception of the value. But the harm of the short-term nature of public markets and the associated “overreaction” to quarterly reports is way overstated. The public market is intelligent and perceptive. It is certainly a better evaluator of a company’s value than any handful of private actors. The market is willing to look past bad quarters, halves, and even years if the opportunity for growth down-the-road is clear and the company’s leadership has a plan.

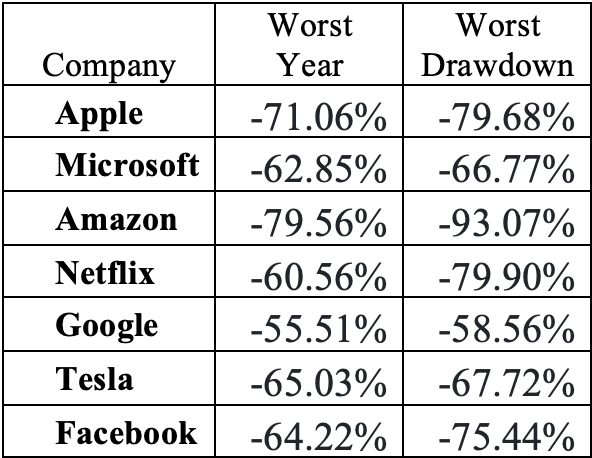

There is a good argument (rarely made) that having more scrutiny and coming to age in the public eye is a net benefit for the health of a company. The public market provides an important signal to companies if some of the wider range of public voices suggest a change in direction, either through commentary or by selling their shares. Public scrutiny seemed to work well for the Magnificent Seven, who effectively managed (and improved) through terrible years and drawdowns:

In terms of costs, there are certainly company incentives around the costs of going public (underwriting is the largest expense), and quarterly reporting is a material ongoing expense. But the cost of capital overall for public companies is lower, and the range of financing opportunities (including at-the-money sales, bond issuances, and secondary issuance) is broader.

In summary, it is difficult to generalize for all companies, and the fair price remains the same in either case, so we will go with later IPOs as being neutral for companies (with a gentle-lean negative for good ones due to a lower cost of capital when public). A bad company without future prospects won’t exist for long in any market.

VC Funds

VC funds are complicated because it is also difficult to put the group in a box. There are pre-seed and seed-focused funds, Series A-focused funds, Series B-focused funds, etc. Generally, the funds that invest in earlier stages write smaller checks and have more time pressure for realizing the return on their investments. Later IPOs and realizing returns over a longer period of a time can be a disadvantage depending on the specific investment or company.

With that said, VC funds also benefit from limited, exclusive access to follow-on rounds or investment opportunities as the companies mature. The later stage the VC invests in, the closer it behaves to a late-stage growth fund. As a result, we will put later IPOs for VC funds in the neutral category (with later IPOs being a very gentle-lean positive, due to access advantages in later stages).

Who Wins

The C-suite

As mentioned earlier, a management team (the C-suite) is separate from a company, though in many ways they are often aligned. The management team of companies and whether they lose or gain from later IPOs is not immediately clear. Like employees, they have stock in the companies. All things equal, they would prefer to convert the stock into ski chalets within a reasonable timeframe.

But unlike other employees, the C-suite has more control, more responsibility, and more directly face consequences if there are suboptimal decisions on the capital markets side (like a decision on when to IPO). The pressure on the management team after a bad year in public markets is intense. While that pressure may be long-term good for the company’s prospects by indicating a need for a change in strategic direction, it can be short-term bad for the current management team.

There are other considerations here, and this group is a more nuanced “winner” than the group below, but no one ever got fired for being private too long, so we will put the C-suite in the winner category.

Late-stage Growth Funds

This group is far and away the biggest winner from the shift to later IPOs. Late-stage growth fund managers (like Tiger Global and Coatue, among an increasing number of others) have more money, power, and influence (often expressed through board seats on the companies) than ever. They continue to grow and get stronger with every fund. Late-stage growth managers are the recently crowned “Kings of Technology”, no matter how many friends they lose, or how many people they leave dead and bloodied along the way.

Philippe Laffont, Chief Investment Officer of Coatue Management, recently said, “In the past, you could go public with a $500 million market cap…[and] $50 million in revenue. Today, we think that you can’t go public without $1 billion in revenue, $10 billion in market cap.” What a curious view….

The Market is Headed in the Wrong Direction

The above is an earnest attempt to represent the general trend of late-stage technology company equity markets and the winners and losers from later IPOs. It may appear from the above that I am suggesting that late-stage growth funds and (to a lesser extent) the C-Suite at companies together have pushed IPOs back to suit their interests, with VC funds and the companies themselves as relatively neutral bystanders. A reasonable reader may think that I see this trend coming at the expense of investors, company employees, and the overall health of the market.

While that is exactly what I am doing, that argument could easily be criticized as an oversimplification given the complex motives involved in each decision regarding IPO timing. Actually explaining the dynamics of each idiosyncratic decision of when to IPO for each company would be a thousand-page document, which no one would read. There are a lot of pieces here in a complicated market and anyone evaluating it must approach the discussion with a “beginner’s mind” and humility. Noted. I am sure someone could argue that the “market is different today,” which I would be curious to read.

However, regardless of the causes, what is certain is the equity market for later-stage technology companies is headed in the wrong direction. Investor access should be improving, not getting worse. Fees should be decreasing, not increasing. Markets should be becoming more transparent, not less. Shareholders should be treated more equally, not less. And liquidity should be increasing, not decreasing. All of those are going the wrong way.

Suggested Structural Changes

There are significant structural changes that would have to occur over the next decade to get the market on the right track again for all constituents. Awareness and clear-sightedness on how the trend of later IPOs is clearly worse for some important constituent groups (such as investors and employees) are a first step. At a minimum there should be regulatory sandboxes, educational or advisory programs that demystify going public for management teams, showing its benefits. This would serve as a counterweight to the current growth-fund-led narrative, reverberating around conferences, regarding the need for companies to remain private longer (see the Coatue quote above). The earlier in a company’s lifecycle these are presented to management, the better. Recent early-IPO successes such as Elastic (6 years), Samsara (6 years), GitLab (7 years), DraftKings (8 years), Zoom (8 years), Crowdstrike (8 years), and DoorDash (8 years) should be highlighted.

There is certainly low-hanging fruit to gently nudge companies on the margins in the direction towards public listings. The going-public process should be significantly streamlined. Modifications to exchange listing requirements could go some ways. Technological improvement and competition within the underwriting process, the largest upfront one-time cost of going public, could help to simplify regulatory filings, investor outreach, and compliance. The government could reduce some of cost disincentives to be public, such as fees or ongoing reporting costs, or alternatively use incentives, such as deferred taxation or credits.

If the low-hanging fruit cannot incentivize the C-suite to take the public leap, more drastic measures would need to be considered. For example, I do not hate the idea of using policy to embolden the management team relative to investor board members (either pre-IPO or post-IPO) to overcome the current incentive-trap problem. Providing management some protections from being fired for performance reasons in the first year or two after going public is an extreme but interesting example. These are the types of ideas that should at least be discussed, given what is at stake. There’s a lot more work to do here, and I’ll be interested in seeing how the public discussion evolves.

The Main Point

Investors used to be able to own the world’s most promising technology companies for free, instead of paying 2% annually, giving up 20% of the gains, and trapping their investment in an illiquid fund structure. They had the chance to turn $10,000 into millions.

Investors can’t do that anymore. Over the coming years, many investors will watch AI companies explode in value from the sidelines. That’s a problem.